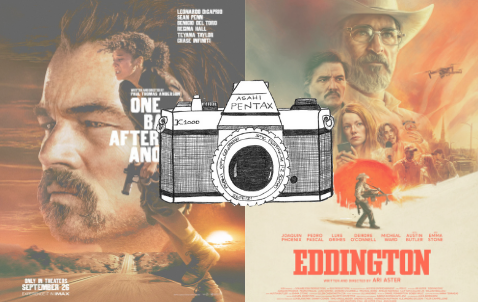

Eddington, One Battle After Another, and the Importance of Empathy

Graphic by Emma Novy

Spoilers for both One Battle After Another and Eddington. Only see the former if you haven’t… you’re not missing much with Eddington.**

Modern cinema needs more westerns. If you’re a more casual movie-goer, you might think of westerns as drab, old-fashioned, unbearably masculine, and brimming with conservative subtext. That being said, I’ve always had an appreciation for the genre for the same reasons I enjoy country music (beyond their shared stylistic qualities I’m accustomed to), in that both have universally recognized tropes/common elements. By utilizing similar song structures and plot arcs, the gaps in craftsmanship amongst creators are easily recognizable, whether it be phenomenal sonic texture and songwriting, or great dialogue and cinematography.

More importantly, though, genres that have clearly established traditions are ripe with opportunity to subvert said tropes in a post-modern approach. This is very prominent around the independent modern country scene, where acts will actively deconstruct the trappings of American conservatism found within the genre and replacing it with something more ingenuitive and universal. I’d actually argue that the greatest acts of the scene (Lori McKenna, Jason Isbell, Orville Peck, among others) are the ones who tear into country’s broken systems while also refusing to shy away from the homespun whimsy of tradition that made the genre so inviting in the first place, a “metamodernist” approach that takes a lot of nuance but when done right, is absolutely wonderful.

By comparison, westerns have yet to fully embrace reinvention. Sure, there are phenomenal “modern” westerns (Django Unchained, No Country For Old Men, Power of the Dog, and Rango, to name a few), but they largely reject a modern lens– their stories taking place in the past or devoid from modernity with a time period that isn’t plot relevant.

If that’s the case, what could make a western “modern”, per se? “Politics and cellphones!”, cried Ari Aster, after the release of his newest film, Eddington. Uniformed media outlets rushed to crown Aster’s fourth feature-length as “the first truly modern western”, as the film takes place in a Southwest small town during the heights of the 2020 COVID pandemic, with much of the narrative emulating the political and emotional turmoil of the time, particularly mask mandates and the Black Lives Matter protests.

Just a few months later, acclaimed filmmaker Paul Thomas Anderson’s One Battle After Another hit theaters, telling an arguably more timely story about the collapse of an American far-left movement called the French 75. With a heavy focus on racial bigotry, far-right spheres of influence, and the realities of anti-immigration policy that makes for natural comparison to those of the current administration.

Despite these superficial similarities, I have equally strong yet wildly opposite views on both films: OBAA is a spell-binding, deserving “Best Picture” frontrunner, whereas Eddington joins the ranks of Don’t Look Up and Civil War for overwrought, pretentious, and deeply unwatchable political satires that genuinely piss me off.

Even on a purely filmmaking level, Paul Thomas Anderson proved his superiority over Ari Aster. OBAA’s cinematography and performances are consistently excellent, while Eddington’s are spotty and underwhelming (how do you underutilize Emma Stone???) For movies both around 2-and-a-half hours, OBAA remains engaging and essential viewing throughout its runtime, whereas each passing scene in Eddington could’ve been cut in half and I would still be looking for the exit. I attribute this to OBAA’s fantastic use of score, utilizing extended percussion loops that slowly build to ramp up the feeling of driving tension, where instead, Aster consistently opts for no music to accentuates feelings of discomfort but only exponentially increases my own boredom.

However, the biggest disparity between both movies comes in framing. One Battle After Another contains deeply human characters whose failures are disappointing, yet understandable, which makes their recovery and improvement on past mistakes quite rewarding to see play out. On the contrary, Ari Aster purposely wrote a litany of unrequited, irredeemable stereotypes in an effort to show how stupid modern America truly is and how smart he is himself for seeing through all the “lies”, which only serves to make Aster the most shamelessly punchable face in all of Hollywood.

A good deal of Eddington’s failures can be found in the film’s lead character Joe Cross (Jaoquin Phoenix). For transparency’s sake, I’m not the biggest fan of Phoenix’s recent acting filmography, which includes another Aster dud Beau Is Afraid, alongside the self-indulgent Joker movies and Ridley Scott’s disaster Napoleon. He’s often stuck playing characters who have internal demons left intentionally vague, but ones where peeling the layers back is less intriguing or interesting than the scriptwriters probably expected. This leads to performances where Phoenix seems lost in his own world, where I’m neither enthralled by the grandeur or care for his struggles, instead just coming across as a weirdo.

Joe Cross is another addition to that repertoire: a middle-aged, deeply conservative sheriff of a small town who overinflates the concept of mask mandates and civil rights protests as the "darndest thing I’ve ever seen” (or something along those lines). He’s also the agitator of the movie’s craziest and least forgivable moments: fabricating a story about his wife’s sexual assault for his own political gain (and to mend their own marraige), murdering mayoral opponent Ted Garcia and his innocent son for publicly humiliating him, and attempting to frame his black officer/protege Michael, in the most frustrating-to-watch sequence in recent memory.

This annoyance is only amplified by the film’s worst feature: the writing. In the grand tradition of hack comedy where “no one is safe”, Aster takes every character of a given political view and reduces them to their most obvious cliches, criticisms and descriptors. There are no multi-dimensional characters with human emotions, just stereotypes of the most insufferable terminally online losers. For Joe Cross, Aster’s lack of care for nuance and good faith commentary results in a bumbling buffoon that doesn’t as much tragically descend into madness but rather goes from unthreatening to genuinely psychopathic on a dime.

This mishandled character work is derailed by a truly incoherent finale where Joe begins mowing down hordes of Antifa super soldiers, who are later revealed to be plants from the nearby data center tech conglomerate, which all serves Ari Aster’s massive bait-and-switch that “the REAL evil in America isn’t Democrats or Republicans, but tech billionaires!” This leads to an ending where a mentally compromised Cross (who detested the data center from the beginning of the movie) gets elected mayor, but ultimately is unable to stop his caregivers from allowing the town of Eddington to fall under greater corporate control.

Let’s ignore the implications that issues regarding surveillance and AI didn’t rally the youth the same as COVID and Black Lives Matter did back in 2020 (even if this past year thoroughly disproves that notion), or that Big Tech hasn’t operated in cahoots with certain sides of the political spectrum rather than being this all-encompassing evil separate from partisan politics. Of course those observations are short sighted, that doesn’t need restating.

What’s more offensive, however, is how Aster treats these commonly held truths as grand reveals, only demonstrating his utter contempt for the average person and his genuine belief that people are so ignorant to the world around them. Are there people who likely need that lesson beat into their head? Yes, I’ve been on Twitter, but considering I’m not part of that demographic, having to sit through 150 minutes of doomscrolling from the world’s most self-absorbed director to come to those mundane conclusions is an abhorrent waste of time.

By comparison, OBAA rises to its greatest highs when it displays unmitigated compassion and adoration for humankind. The film is brimming with joyous energy: the opening sequence showcasing the French 75’s jubilation while breaking out detained immigrants is a genuinely uplifting note to start off on.

There are plenty of easily likeable characters, whether it be young hero Willa Ferguson (played by Chase Infiniti, who gifts Willa a phenomenally youthful, yet earnestly fiery demeanor), or Willa’s sensei Sergio (Benecio del Toro), whose partnership with Dicaprio’s Bob Ferguson makes for phenomenal buddy-cop camaraderie.

It helps that the film refuses to straddle the political fence. Your heroes are far-left revolutionaries whose intentions are pure but falter when ideals clash with reality (ain’t that real), while your antagonists are a far-right cult of uber-powerful white men whose goal throughout the movie is to assassinate one of their own for not being racist enough. Like Eddington, OBAA also contains a scene where agitators are intentionally planted to villainize protestors, but instead of treating it like some massive reveal, it’s instead acknowledged as the frustrating reality most social movements must contend with, and actors act accordingly to support one another against state violence.

Despite his best efforts, Paul Thomas Anderson received some blowback in leftist circles, specifically around the choice to make Perfidia (the black French 75 de-facto leader portrayed by Teyana Taylor) rat out the rest of the revolutionaries following her capture early in the film, stigmatizing her character throughout the rest of the movie. A similar situation occurs when the villains infiltrate a school dance in pursuit of Willa, where many online were frustrated that the one friend willing to give over her phone number was Hispanic and non-binary.

While many watched these characters making difficult, self-motivated decisions and saw it as PTA condemning minority groups, they ignored the larger context of these scenes. Unfortunately, marginalized people when placed in do-or-die situations are under even tougher pressures to capitulate, as their punishments may be more severe. These are not nefarious traitors, but rather victims forced to make lose-lose decisions, which when placed intermittently across the narrative, only accentuate the feeling of hope dwindling away. This allows the final moments of the film–Willa’s defiant last stand, her reconciliation with Bob, and her desire to keep fighting against injustice despite all the turmoil she’s been through–to shine brightly optimistic.

One Battle After Another will be the subject of many thinkpieces to come, especially once Oscar season rolls around and it inevitably receives dozens of nominations. While I expect that increased attention to result in newfound scrutiny for its themes and political messaging, the overall impression the film leaves on me is overwhelmingly positive, and should inspire any young adult to go out there and make a difference. At least it’s better than Ari Aster’s ideology of utter contempt.