I Have a Dream

Becoming a U.S. citizen is simple: Mama got to birth you here. For those who aren’t so lucky, obtaining U.S. citizenship by law can be an excruciating process.

The Development, Relief, and Education for Alien Minors (DREAM) Act—if it ever passes through Congress—would ease that long and tedious process by offering certain illegal immigrants an easier path to obtain a Conditional Permanent Residency through higher education, or service in the military. And when I say the act only applies to certain illegal immigrants, I mean certain illegal immigrants. Tons of requirements stand between them and a green card. Applicants must have entered the country before their 16th birthday, lived here at least five years, and graduated from high school or obtained a GED. But these requirements are just the beginning. After an acceptance to this conditional status, applicants are required to live a six-year term of probation, submit to background and criminal checks, and expected to cover any living expenses. These children, often forced to become illegal by parents sneaking into the U.S., try to start a life in a new country with a different language and culture. Let’s admire them, not kick them out of a country they’ve called home for over five years.

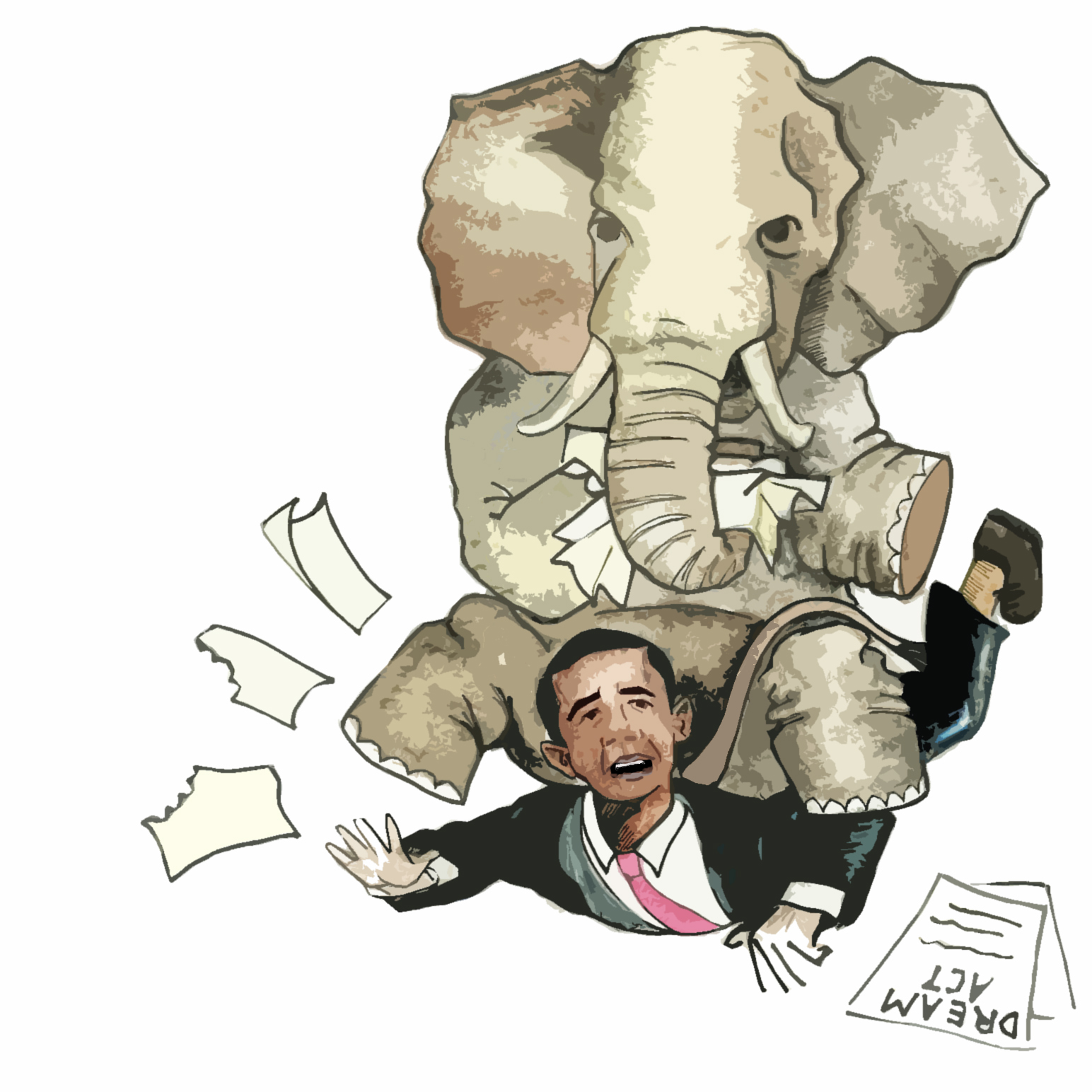

While both the Republican and Democratic parties participated in the drafting of the DREAM Act, confrontations still arise as to who’s on what side. This act brings out an issue that democracy has had since, well, forever: estos hijos-de-putas (those sons of bitches) that don’t work for their constituents. Who cares which political party got the idea first? Blame those right-wing bastards. The DREAM Act Portal website reported that Utah Senator Orrin G. Hatch (R) voted against the act because it was brought up by the Democratic party. No wonder the majority of the senators who voted against the bill were Republicans. Yay peer pressure.

If senators find issue with the way the act was brought up, they probably actually have an issue with the act itself. The government is still deciding whether to change the period of conditional status from six years to 10 years. Sure, then the act really helps these people. They’ve lived here for years already, as minors no less. Those who benefit from this act had no say in entering a country illegally. It doesn’t make sense to put a timeline on American freedom for those who might have never asked for it, but earned it.

It may take years, and, let’s be real, a large amount of money to get the bill back on track, but the DREAM Act could open a lot of doors for a lot of people who not only need it, but deserve it as well. President Barack Obama acknowledged the need to pass this act and promises to see it through while in office. At least he recognizes that making citizenship a little easier for a group of educated, service-driven people is a good idea.

Some may be worried about those damn immigrants stealing American jobs. But these are Americans, just Americans with irresponsible parents who couldn’t make them legal before crossing the border. We shouldn’t punish the children of illegal immigrants by calling them outsiders when this is the only real place they’ve called home. The DREAM Act doesn’t make the road to legalization easy for young illegal immigrants—just a little bit easier.