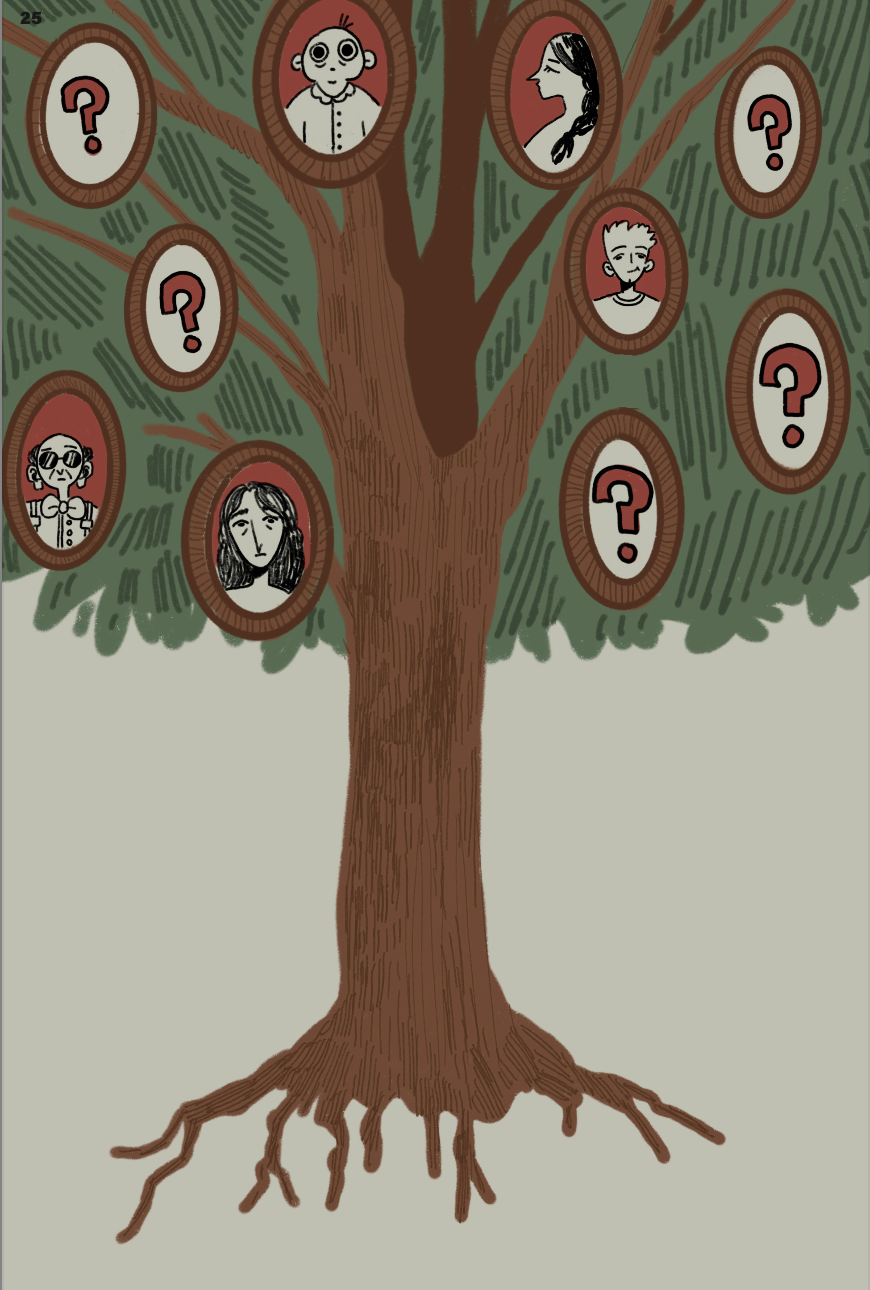

DIGGING UP YOUR ROOTS

Art by Alex Youngquest

First, make a huge outline of a tree. Then, cut and paste some pictures onto a poster board. Next, draw some lines connecting family members until they lead to you.

These are the steps to create a basic family tree—a classic elementary school project. It’s a fun craft to put together with the help of your parents as a child, but as you grow older, it becomes more than just a poster project to present to your classmates.

For many, the search for belonging and a concrete sense of identity is fulfilled by understanding their roots. Especially within the context of the United States, a country where the majority of citizens’ origins are tied to immigration, exploring ancestry can help people make sense of how they’re living today.

Today, ancestry can be traced using a variety of different methods, the most modern being services that allow individuals to submit DNA samples and analyze their results online. The “big four” companies that provide this service are AncestryDNA, 23andMe, MyHeritage and FamilyTreeDNA.

By 2019, more than 26 million people had added their DNA to these companies’ ancestry and health databases, according to MIT Technology Review. Users send their samples either in the form of saliva or a buccal swab with materials provided from the test kits.

From there, the companies process the sample using your autosomal DNA, the genetic material inherited from both parents that determines your traits. It’s used to pinpoint genetic markers called single nucleotide polymorphisms, where the DNA tends to differ from person to person. Since most humans share 99% of the same DNA, these markers help trace lineages because they are inherited from individuals’ biological parents.

With services readily available and accessible right from people’s homes, DNA testing has become a popular gift, especially during the holidays. But each person’s reason for trying a test differs.

Cate Vickery, a Syracuse University senior, has seen her ancestry traced all the way back to the 1600s. But she did not complete the research herself—the process is a personal hobby of her grandmother’s that has since turned into a way for her to meet distant relatives.

Vickery was never really interested in her family’s history until she was given a high school project to create a basic family tree going back two to three generations. From there, she discovered her family has had roots in America for more than 400 years, since before its establishment as the United States.

A fun tidbit she found? Every firstborn son on her mother’s side of the family was named John. “It goes back hundreds [of years]—they're all John. Even if there's multiple siblings, the firstborn is always John,” Vickery said. “And I think that's really funny because my mother decided to not name my brother John, his name is Thomas.”

These are just some of the small, yet amusing things tracing your roots can uncover. Vickery’s grandmother pays for an AncestryDNA subscription, which allows access to more complex records.

Census documents from towns her relatives lived in and birth and death certificates are public records Vickery’s grandmother used to piece together their family tree. Lots of information was also passed down by word of mouth.

Now, with accessible digital tools, Vickery’s grandmother created several ways to keep everything saved for future reference with multiple flash drive copies, journals and books.

Access to such materials is essential to trace back ancestry, which is a privilege not afforded to marginalized groups. Natalie Novotna, a forensic science professor at SU, explains that one primary reason is simply that most people who do voluntary DNA testing of this nature are those of Western European descent. Consequently, Black, Latin, Asian and other communities of color are left out of the databases.

AncestryDNA outlines on their website that their calculating customers’ results relies on a database of DNA samples, “collected from people with deep ancestral roots in certain geographic regions.” For those who aren’t of Western European descent, this could mean less detailed, potentially inaccurate results.

“If you upload your profile and you're hoping for a [match] from these minorities, the chances are smaller that you're gonna get a hit,” Novotna said.

DNA testing is not only used for ancestry purposes, but also health ones. It can tell people if they’re at risk for certain genetic diseases or conditions, which can aid with decision-making about prevention and further screening.

According to a 2025 study done by Jemar Bather, Melody Goodman and Kimberly Kaphingst, people living in “high vulnerability” neighborhoods— which refers to areas disadvantaged by socioeconomic status, household characteristics, racial and ethnic minority status, housing type and transportation—are less likely to use genetic testing services.

Lack of healthcare access and poor infrastructure impact the resources available to perform DNA testing, making for less awareness and experience with these services, and leading to medical risk algorithms being biased against non-white patients.

Genetic testing can be expensive, which poses another barrier for communities of color.

“It can get costly, especially if you want to look more into the lineages and try to enter multiple different databases to search for potential matches or partial matches—like if you're somehow related, maybe to this person who also entered the database,” Novotna said. “Stuff like that, or even these more involved, more complex forensic analyses might get a little bit costly.”

Furthermore, histories of slavery, colonization and discrimination caused the large gap in recordkeeping because of poor maintenance, incompletion or plain nonexistence. This makes the records that are available potentially unreliable. Historically, government records worldwide did not keep accurate documentation of people and families of color.

Knowing one’s roots may have different meanings for different people, depending on someone’s purpose for digging into the past. It’s a natural inclination to try to understand who and what made you who you are when we spend our whole lives trying to explain it to others.

Now that she’s older, the process carries more weight for Vickery, especially because she has a small immediate family.

“When you think about life, it's your parents and your grandparents, but really, there's had to be so many different combinations of people who I’m related to who've had to get married and have had kids for me to be alive,” Vickery said. “It's crazy how many people I'm related to and I could be distantly related to so many other people who I don't even know.”