Writings on the Wall

Parents and friends use Facebook to cope with the loss of their loved ones

By Jessie Assimon

Michael Goodman, a 53-year-old technology consultant, regularly logs onto his daughter’s Facebook account. He changes her profile picture, updates her status, reads her wall posts, and accepts gifts and bumper stickers sent from her friends.

His daughter, Bailey, died on June 26, 2007 in a car crash with four of her best friends five days after her high school graduation. Updating Bailey’s Facebook profile helps Goodman keep his daughter’s memory alive.

“I will occasionally change her profile picture, and once in a while I might put a message in the category ‘what’s on your mind?’” Goodman said. “When everybody went back to school this year, I put a note up that said ‘good luck to everybody.’” He also rotates her profile pictures according to the time of year. This past spring, he posted a picture during prom season of Bailey and her friends in their dresses.

The advent of Facebook has modernized the way parents and friends cope with grief. It gives them a readily accessible way to communicate with their dead friend or loved one by posting comments on their Facebook wall, creating tribute groups, and viewing and posting old photos. For a generation that grew up during the peak of the online era, it’s natural for young adults to start using the Web to deal with emotions like grief, said Carla Sofka, an associate professor of social work at Siena College in Loudonville, N.Y. Sofka wrote a chapter on using the Internet as a coping mechanism in a book on grief entitled Adolescents, Technology, and the Internet: Coping with Loss in the Digital World. “I think that’s just phenomenal when it gives people a socially acceptable outlet for their grief,” she said. “That’s not a real easy thing to find in traditional ways.”

Spencer Goodman, Michael’s son and a 2009 Syracuse University graduate, said Facebook helped him cope with the death of his sister Bailey in a way that face-to-face interaction with a therapist would not. Spencer said he would have felt out of his comfort zone if he had to talk to a “professional” right after Bailey’s death. But when sitting at the computer in his Euclid Avenue apartment, he could still communicate with Bailey’s friends across the country who offered their condolences and shared similar emotions.

Spencer created the Facebook group “Bailey Goodman: Loving Sister, Friend, and Daughter” the day after the accident. Through the group’s 1,379 members and 99 photos, he found a way to manage his grief. Some of the comments posted by group members made him smile.

“For the first six months, it was a big help because like I said, I don’t really like to talk to people. And being a psychology major, I understand what a shitty idea that is to have your sister die and then just not talk to anyone about it,” he said. “Facebook gave me the opportunity to express myself and let out my feelings.”

Justin Leonard, a senior broadcast journalism major at SU, used Facebook to cope with the loss of his fraternity brother, Matt Wanetik. Wanetik died from Sudden Arrhythmia Death Syndrome last year while studying abroad in Strasbourg, France. “There was one night where my friends and I sat around talking about him, and the first thing I did after the conversation was go on Facebook,” Leonard said. He used Facebook after the conversation ended because he said it offered an “interactive view of Matt’s life.” Seeing photos of Wanetik and reading the memories people posted on his wall comforted Leonard and helped him remember his friend’s vibrant life.

In the pre-social networking site days, dealing with loss was less interactive and those struggling with the death of loved ones often felt isolated and alone. Grief expert Heidi Horsley, who counsels people through her radio show, her Web site, www.thegriefblog.com, and TV appearances nationwide, sat in Spencer’s position when, at the age of 20, she lost her 17-year-old brother Scott in a car crash. Horsley said friends could only listen to her vent for so long because most of them couldn’t relate to her situation. She avoided talking to her parents, trying to spare them any more pain after losing their son.

Horsley said she wishes a Web site like Facebook existed then for her to use. “I could’ve gone on the Internet and seen that other people have also had the death of a family member and they had survived,” she said. A related concept called “continuing bonds” first appeared in 1996 in Phyllis R. Silverman’s Continuing Bonds: New Understandings of Grief. Silverman says that after someone dies, each person needs to find a way to maintain a connection with the person they lost. And until the 20th century, society accepted the continuation of bonds between the living and the deceased.

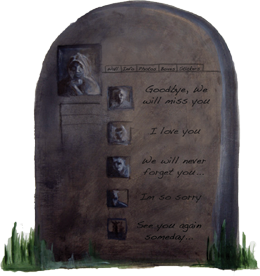

Sofka sees young adults using Facebook to grieve as an “innovative way to establish that continuing bond.” Acting as a virtual gravesite, Facebook profiles enable users to stay connected to their dead friends by communicating with them through wall posts. Some friends share fond memories, while others simply post whenever their friend crosses their mind.

Grief specialists say one of the benefits of using Facebook to cope with such loss is that the Web site is available 24/7 for people to vent and recover. If someone wakes up in the middle of the night and needs to write to their friend or look at pictures for comfort, they have an easily accessible outlet.

That ongoing availability has helped Michael Goodman stay connected to his daughter by reading posts friends leave on Bailey’s Facebook. Gloria Horsley, Heidi’s mother and a fellow grief specialist, said it’s natural for parents to want to access their dead child’s Facebook account and monitor what’s circulating on the Internet about them. Michael Goodman said on Bailey’s Facebook profile. Gloria Horsley, Heidi’s mother and a fellow grief specialist, said it’s natural for parents to want to access their dead child’s Facebook account and monitor what’s circulating on the Internet about them. Michael Goodman said he’s learned things about Bailey he probably would never have known had her friends not shared them on Facebook. “As a parent who lost a child, some of it’s comforting to know that the time and effort we put into raising her, it was worthwhile — that she was a good person, that she made people laugh, that she did good things for people,” he said.

Grief specialists say one of the benefits of using Facebook to cope with such loss is that the Web site is available 24/7 for people to vent and recover. If someone wakes up in the middle of the night and needs to write to their friend or look at pictures for comfort, they have an easily accessible outlet.

That ongoing availability has helped Michael Goodman stay connected to his daughter by reading posts friends leave on Bailey’s Facebook. Gloria Horsley, Heidi’s mother and a fellow grief specialist, said it’s natural for parents to want to access their dead child’s Facebook account and monitor what’s circulating on the Internet about them. Michael Goodman said on Bailey’s Facebook profile. Gloria Horsley, Heidi’s mother and a fellow grief specialist, said it’s natural for parents to want to access their dead child’s Facebook account and monitor what’s circulating on the Internet about them. Michael Goodman said he’s learned things about Bailey he probably would never have known had her friends not shared them on Facebook. “As a parent who lost a child, some of it’s comforting to know that the time and effort we put into raising her, it was worthwhile — that she was a good person, that she made people laugh, that she did good things for people,” he said.

Besides using Facebook as an outlet to communicate with dead loved ones, the site serves as a virtual shrine built around the hundreds of pictures people post of their deceased friends. Spencer Goodman, who kept one framed 4” x 6” photo of his sister Bailey in his bedroom at SU, uses Facebook to look at more pictures. Similarly, photos of Wanetik in Israel and at a Philadelphia Phillies game ease Leonard’s pain when he visits the site because Leonard said, with a grin, that he can view “Matt in his glory.”

Other people use Facebook not only to express their feelings through posts, but to share tribute videos. Terron Moore, a senior communications and rhetorical studies major, posted a video of a dance he choreographed following the death of his friend, Gleidy Epsinal. Espinal, a former SU student, committed suicide last fall while studying abroad in Madrid, Spain. The video, in which Moore tagged Espinal, shows Moore and a friend dancing to Alicia Keys’s Like You’ll Never See Me Again. Moore said the video helped him cope with the grief and pressure he felt when he heard the news of her death. A family member of Espinal commented on the video. That comment, among others, made posting the video worthwhile for Moore.

Moore said he sees visiting dead friends’ profiles on Facebook as a cheerful outlet. “No one puts bad pictures up,” he explained. “You remember jokes and funny things.”

Meanwhile, Wanetik’s fraternity brother Leonard said there’s a downside to letting people post on his dead friend’s Facebook since the site lacks a filter. “Someone who didn’t like them can use that opportunity to write negative comments on their wall,” Leonard said.

As time passes, people tackle their grief and their activity on dead friends’ Facebook profiles decreases. And although they stop actively posting, memories of their friends live on.