Algorithmically Inclined: Jesse Stiles

By Eric Vilas-Boas

Automatic Speleology adds light, color, and excitement to the Warehouse's Window Projects

The bearded Jesse Stiles peers at a laptop on a folding table in the middle of the Warehouse Gallery in Downtown Syracuse. Three rapidly changing projections of random images play on the whitewashed walls around him. Computer chips, microprocessors, LED spotlights, and slabs of wood surround him and his robot designer Mike McAllister. The clutter is his work-in-progress.

Stiles is a new media artist and an electronic musician. He freelances for various multimedia projects and has taught university-level courses in sound production. His first solo exhibition, “Automatic Speleology,” will be featured at the Warehouse Gallery until May 29 and includes live robotic drumming, electronic music, high-definition video and photography, and a multi-colored light show, all set to randomized algorithms. Stiles’ body of work straddles the line between the commercial and the strictly artistic.

Anja Chàvez, the curator of contemporary art at the Warehouse, traveled to Stiles’ home in DeRuyter, N.Y., last year to try to bring his work to the Warehouse. “It was so clear,” she said, reflecting on the first couple of hours she had spent with him. “You could see his brain was just working constantly on so many very good ideas.”

Stiles titled his project Automatic Speleology, referencing the scientific study of cavernous spaces, to show his admiration for speleologists who attempt to discover the secrets of the earth through exploration. He relates that sentiment to his artwork by exploring deeper meanings embedded in the different media he utilizes.

Stiles described Automatic Speleology as a “completely generative” show. “Nothing in the show is being repeated,” he said proudly. “There are no looping patterns. Everything is being generated as you observe it.”

These algorithms constantly re-edit the five channels of video footage projected on the walls and the six channels of sound, each playing through a different loudspeaker. Throughout the videos, people walk around, snow falls on still objects, and tracking shots meander through empty roads in the night. The images loom, darkly omniscient, and display much of the past year of Stiles’ life. Outside the gallery, the LED lights — on loan from Stiles’ friend and fellow artist Carl Gruesz — strobe to the beat of the algorithm, backlighting the robotic drummers that pound on the glass windows of the Warehouse with rubber hammers, perfectly in sync.

The robots were designed by McAllister and built with help from his students at the University of the Arts in Philadelphia. Stiles and McAllister predict that the drummers will hit the windows almost 9 million times by the end of the exhibit’s run.

“They’re all puppets, and I’m the grand puppeteer,” Stiles said. The whole show is purposefully integrated to create a multisensory experience that hits an audience just a song would. “[When I’m] creating systems that are going to rapidly re-edit things, I’m thinking about a drumroll, I’m thinking about 32nd notes...I’m thinking about textures the way you might think about arranging a song, but the textures might actually be visual.”

Starting in August 2000, to August 2001, Stiles lived on the Watson Fellowship for a year. The grant for a post-graduate independent study abroad allowed him to club-hop in London, fight off monkeys in India, and tour the Australian Outback, all while picking up music tips and recording local music.

After returning from Australia in August 2001, he released Watson Songs, an album combining his own music with samples he recorded during his year abroad, and enrolled in graduate school at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, where he decided to start building his own tools to make music.

“That was really when I opened the floodgate to all these other media that I’m working with now,” Stiles said. “This idea that music is two channels of sound in stereo is this arbitrary thing that came out of the recording industry. All these programs that you get out of the box are for helping you make two channels of sound. As a musician that’s a crazy thing to limit yourself to.”

Designing his own software tools — which he had never attempted before graduate school — helped Stiles express himself while staying true to his past experiences. A graduate education gave him his first taste of creating algorithms, as well as working in conjunction with multimedia artists.

In India, Stiles learned as much as he could about classical Hindustani music — a Northern Indian musical tradition — particularly the integral concept of the raga. The raga is a series of 12 notes that a musician can use to compose a melody. Unlike Western music, which is divided into major and minor keys, the 12-note raga is further divided into seven-note “thats,” which a musician is free to use and experiment with.

“Because Indian music is improvised, it’s a great model for what I do, which is kind of improvised by a computer,” Stiles said. “A raga is really a set of rules, the way that this show is just a lot of rules … [The 12 notes in a raga] have different relationships to each other and one of them is the center. Performing the raga is about exploring the possibilities of these rules and returning to this central tone.”

Though Stiles’ equipment appears to limit his ability to express himself, he does not find his constraints debilitating. While preparing for the exhibition, Stiles worked with nine spotlights, five projectors, six loudspeakers, 12 robots, three glass resonators, and three computers.

“It’s all about building a structure that has limitations, and you find out what you can do inside of it,” he insisted. “Having no limitations would actually be a problem.”

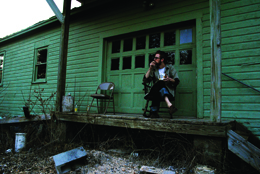

Like his artwork, Stiles’ life moves spontaneously. He was willing to embark on impromptu, month-long electronic music tours along the Rust Belt, while making his way to and from Chicago for an improvisational music and dance presentation. He rents an old textile mill with his girlfriend Olivia Robinson in DeRuyter — just 30 miles south of Syracuse — where he lives today.

Even the rigid robots that power the live drumming in Stiles’ performances have the same element of spontaneity, according to industrial design veteran McAllister. Working with a mill typically takes a lot of precision, but McAllister talked about making cuts to metal pieces based on spur-of-the-moment intuition rather than planning. “It’s kind of this funny balance between loose and tight,” he said, describing his production style. “And I think that’s true of [Stiles’] music.”

Robinson, who worked as a production assistant on Automatic Speleology, describes Stiles’ latest project as less marketable than more traditional art pieces, which can be easily valued, bought, and sold. “The Red House sometimes brings in people who are doing things with lights and audio, but this is particularly very different from what’s gone on in galleries at SU,” she said.

Stiles said he was very impressed with the Warehouse’s openness to his project, and delighted in the resources they provided him, including the space, projectors, and sound system.

Chàvez said that the Warehouse strives to present artists that operate in various media and truly matter in contemporary art. “The larger community may not necessarily have seen [Stiles’] kind of art,” she said. She hopes that many different members of the Syracuse community will attend the exhibit.

Attendees young and old mixed it up on the dance floor at Automatic Speleology’s public reception and dance party at the Warehouse Gallery on March 25. Stiles spent the night explaining his artistic process to guests and broke up the presentation with his two-hour DJ set, using a laptop and mixing board. He played poppy, dance-oriented tunes that melded with the images on the screens around him, an effect only improved by his guests’ intermittent dancing. The windows quickly bruised with visible rubber track marks where the robots struck the glass panes.

“There were four people standing outside in the rain just staring at [the robots],” McAllister said. “Kinda one of those weird things, you know, it was like, ‘Wow, it was worth it.’”

Stiles plans to release two albums later this spring. He described one as a “bubblegum pop” record, featuring a variety of instruments as well as what he called “imaginary instruments,” or sound effects created independently that emulate real instruments.

Despite the fact that his performances can work in both dance party pop music venues and high-art locales, Stiles classifies himself as neither a mainstream artist nor an art-gallery staple. To him, those distinctions only hold artists back. “Once you say ‘This is me, I’m in this band, this is what I do,’ you’ve closed the door on a lot of things,” he said.

In the end, it all returns to Stiles’ original metaphor for Automatic Speleology. “Where everyone else in the world says, ‘All right, we need to turn around — get the fuck out of here,’ the speleologists would say, ‘I think we can go even further in.’”

photography by Devanshi Tripathi