In High Gear

By Julia Askenase

Once a vacant warehouse, the Gear Factory could reshape Syracuse's creative landscape

In mid-60s Manhattan, The Factory served as Andy Warhol's studio, a place where the iconic pop artist produced many of his famous silkscreens. But it also became a gathering place for fashionable creative types, celebrities, and social oddities. The Velvet Underground played there. Sometimes Bowie dropped by. Many movies--like the recent Sienna Miller flick Factory Girl--would later document the scene. The Factory went down in history.

Today, a different kind of factory resides on the corner of South Geddes and West Fayette Streets in the Near West Side of Syracuse. There are no celebrities. There are no pretensions. And in some parts of the building, there is no heat. But a similar kind of creative energy flows within its reinforced concrete walls, where local innovator Rick Destito provides studio space and creative freedom for artists and musicians. The Gear Factory--once just another vacant, dismal-looking warehouse in a declining neighborhood--has become an artistic meeting ground on the verge of expansion. And if things play out as Destito envisions, it could put Syracuse on the creative map.

"I've traveled around the country, and I've seen a lot of places just like this, except they're already done up," Destito said. "They're already established. There are so many opportunities for people to get in at the ground level right now in Syracuse."

Four years ago, Destito transformed these thoughts into actions. After getting the wanderlust out of his system in cultural meccas like Nashville, Tenn., he took a chance on the Salt City. He knew of a vacant warehouse ripe for renovation, but local developers clashed with his vision. They saw a building in disrepair in an area blighted by crime. When they turned him down, Destito, who has a degree in construction management, bought the building himself. With the help of Jeff Jones, his first Gear Factory tenant, Destito refurbished the place and turned its rooms into much-needed studio space for area artists and musicians. It boasts some 30 tenants today.

The third floor of The Gear Factory induces sensory overload. Colors splash from every direction, and an assortment of objects appears entirely random, yet purposefully arranged.

A few feet from the stairwell stands "Mr. and Mrs. Darth Vader," a mixed-media sculpture composed of facing mannequins retrofitted with Darth Vader masks. Between them is a glass Timex display case filled with dinosaur toys and nativity scene figures. The piece will someday include audio that mimics the Star Wars villain's notorious breathing pattern in complementary male-and female-sounding varieties.

Guy Carlo, a 29-year-old Syracuse University graduate student completing his M.F.A. in video art, created the Vaders and several other works-in progress on the third floor. Carlo uses several types of media in his work, but focuses on what he calls "multi-channel installation‚"-- a variety of video channels to form a single composition.

The lingering antiquity of this historic building creates dramatic juxtaposition with the modern art that now occupies its space--and Destito has no desire to part with it. "You can spend millions and millions of dollars on a new building, but for no amount of money can you purchase history or stories," he said.

Erected in 1906, the warehouse originally housed the Brown-Lipe Gear Company, the largest gear distributor in the world at the time, according to Destito. The architect, Albert Kahn, was renowned for using reinforced concrete and natural lighting.

Installation artist Tina Zagyva enjoys the "element of grit" she encounters while working in the old building. For instance, the third floor has no heat. "You'll see us all bundled up just trying to work," she said, laughing. "But it kind of humbles us."

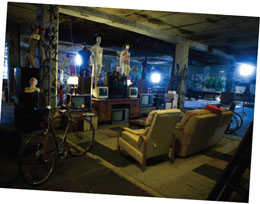

There's also a sense of adventure within these old, sometimes peeling walls--whether it's in riding the industrial elevator, climbing the ladder to the roof, or discovering unexpected nooks and vintage details. Carlo taps into this element of "play" on the wide expanse of the communal third floor. He installed a pool table, an Atari 2600, and an entire dance floor, which complement his off-kilter sculptures. "I set up this floor like I'd set up a living room if I had a living room this size," he explained.

He even erected an "indoor living room," an eye-grabbing installation somewhere between an art piece and a hangout area. A mustard-yellow couch and two wheelchairs face an arrangement of six TVs with mannequins on top. "There are no rules here," Carlo said. "Within safety and reason, you can do anything. There are certainly things you need to run by Rick [Destito], [but] if you want to put up a 14-foot sculpture and leave it up for two months--that‚'s not a problem. There's the space for that."

This atmosphere of artistic freedom transcends every floor of the factory. Up a flight of stairs, guitarist and sound engineer Brett Welts splits rehearsal time between his two bands, Lebanese Blonde and The Black Lotus Conspiracy. When he isn't churning out reverb-drenched alt-rock, he works sound-engineering gigs at The Westcott and Lost Horizon, or runs the music at the Half-Penny Pub. "I love that with my crazy hours, I can come here any time I want and fire up my amp and not get the cops called on me," he said.

Rehearsals at The Gear Factory help distinguish it from some other gallery-and-studio outlets in Syracuse. The Delavan Art Gallery and Center, which resides just a half-mile east down Fayette Street, does not accommodate musicians. "We don't handle that very well because the sound just travels throughout the building," said Bill Delavan, the owner and art director.

At The Gear Factory, background music is an expected component of the overall experience. "It's nice to have the commotion," Zagyva said. "You'll have three bands playing at the same time." For Carlo, listening to a band rehearse often becomes indirect collaboration; a chord progression that floats down to his studio might influence his latest work.

Destito also thinks The Gear Factory appeals to a different type of artist than the Delavan does. "We're not really competing as much as we are complementing each other," he said. "I think [Bill Delavan] gets more of an established artist. I have a little bit of everything--but I've been getting a bit more of the progressive, developing artist."

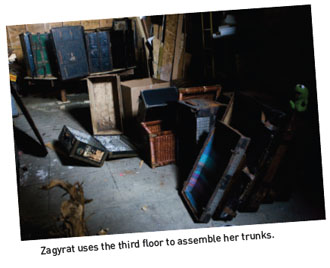

Zagyva, an emerging artist and M.F.A. student at the Maine College of Art, strays outside the conventions of traditional art. Her work wouldn't fit neatly on a gallery wall. She creates "immersive environments," which combine elements of performance, sculpture, and narrative. Her most recent project involves piecing together antique trunks to form a post-apocalyptic "experience machine" where people will be able to crawl inside.

The Gear Factory arrives at an exciting time for the Syracuse arts community. Amy Komar, coordinator of the Th3 arts open that boasts free shows at 24 different venues, has noticed an increase in the sustainability of area art galleries over the past five years.

Although it features the occasional show, The Gear Factory does not constitute a functioning gallery like the Delavan or nearby Red House Center. But Komar said she thinks The Gear Factory adds something unique to the scene. "It's one thing to have a lot of institutions with galleries and stores," said Komar, who works with long-standing venues like the Everson Museum of Art. "But it's really critical for a group like [Destito's] to provide space for all artists to show their art--to be a voice for contemporary art. I don't think an arts community can survive without it."

But Destito dreams of more for The Gear Factory, which is still a private, locked space: The basement will turn into rehearsal space, the first floor into a joint gallery-and-cafe, the second into art-work space, the third into artist-in-residence space, the fourth into livework space, and the roof into a public park.

The thought of expansion, however, rouses a lovingly protective nature in some tenants. "This is a really remarkable period of time. [The Gear Factory is] teetering on the edge of staying as it is and taking off," Zagyva said. "Part of me really wants it to succeed. But I like this moment, and I want to revel in it."

Destito also foresees changes beyond the warehouse walls. The Gear Factory stands at the crossroads of Tipperary Hill, Downtown, and the Near West Side, a current focus of community redevelopment. He hopes to bridge these neighborhoods by changing people's perceptions. "When you drive down a street like Fayette and all you see are busted-out windows, blacktop, and concrete--you know, buildings with frowns on their faces--it's depressing," he said. "The first step is changing the focus from the problems to what [the area] can be."

He envisions bike paths, Lipe Art Park in full force, and the strip of Fayette Street lined with factories just like his own becoming a cultural destination similar to Downtown's Armory Square.

Yet Destito remains realistic about finances and knows these things take time. "The No. 1 priority is making enough money to continue moving on, being able to sustain things," he said.

Standing on the roof of The Gear Factory, Destito points downward to the former Lipe Shop--now a hardware store--where some 360 patents were made. It was another kind of factory; many called it an idea factory. "While that was more on the invention side [of things], it's like 100 years later, we're doing almost the same thing," he mused. "But in a progressive, artistic way."